Illustration from ‘Natural history of western wild animals and guide for hunters, trappers, and sportsmen’ by David W. Cartright and Mary F. Bailey. Toledo, Ohio; Blade Printing & Paper Company, 1875.

Viewable on BHL at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/89577#page/9/mode/1up

“Of all the creatures that inhabit the river at this season the Musk rats are by far the most interesting,” William Brewster wrote in 1894.

That was not to say that he’d seen nothing of interest around his cabin in Concord, Massachusetts; the ornithologist just had a real soft spot for muskrats. He enjoyed having muskrats and other small mammals for neighbors at his cabin and kept a close eye on their whereabouts, recording his observations on their behavior with the same dedication he gave to his bird notes.

An amusing story about an 1892 muskrat encounter shows just how fond he was of these animals.

Spent the entire forenoon at the Buttricks' landing watching the brood of young [Northern] Flickers and the muskrats. There were four of the critters in my boat house under my canoe and a fifth beneath the boat house in the water. I drew out the canoe without disturbing them and then crawled in.

When I was within about four feet of them three scuttled across the house and plunged down through a crack between the boards into the water. The fourth remained perfectly still and presently began to scratch his head with his hind paw.

I cautiously thrust out a long straw and assisted. He started and showed his teeth for a moment turning on the straw as if to bite it but soon quieted down again when, dropping the straw, I substituted my forefinger and, of course, now worked to much better advantage, at first giving the back of the head a thorough scratching, next taking the sides of the neck and finally stroking the back down to the tail.

It was difficult to realize that I was actually handling a wild and perfectly free muskrat for after the first slight show of resentment no kitten could have been gentler and more confiding. In a little while the eyes began to close and the animal gradually sank down on one side and was soon apparently fast asleep.(July 7, 1892. Concord, Mass.) [Edited with line breaks for readability.]

![Illustration from ‘The wild beasts of the world’ by Frank Finn. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, [1909?].](https://library.mcz.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/styles/os_files_xlarge/public/library/files/wildbeastsofworl01finnrich_0301.jpg?m=1515823186&itok=8nYVIFuB)

Illustration from ‘The wild beasts of the world’ by Frank Finn. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, [1909?]

Viewable on BHL at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/62924#page/7/mode/1up

When keeping more of a distance, he still kept a close eye on their behavioral routines, as in the following notes from 1894.

As far as I can make out they [muskrats] all spend the day in holes in the banks and visit their houses and feeding grounds only after twilight has begun falling. Many of them have to cross the river for this purpose and I have noticed that each individual regularly crosses in the same place. The first come out of their holes soon after sunset if the weather is clear, earlier if it be stormy or cloudy.

Some evenings they are very bold – in fact perfectly fearless – swimming about on the open water in every direction and allowing me to paddle past within a few yards without apparently taking any notice of me.

At other times, however, they are so wary and suspicious that I do not succeed in getting so much as a glimpse at one although as I round the bends I see the silvery furrows when they have just dived and everywhere ripples rolling out of the thickets of button bushes or willows when they have been feeding. I am quite unable to understand this difference in behavior or to correlate it with any peculiar or particular conditions of the weather.

During the autumn Muskrats are sure abroad by day much less often than in spring or summer but occasionally during the past month I have surprised one taking a sun bath in a bush when the sun was warm & the water cold. Only twice during this period have I heard them make the low murmuring sound so often given in spring and not once have I smelt their "Musk" (October 11 to November 21, 1894. Concord, Mass.) [Edited with line breaks for readability.]

Illustration from ‘Nature neighbors, embracing birds, plants, animals, minerals, in natural colors by color photography’ by Nathaniel Moore Banta. Chicago; American Audubon association, 1914.

Viewable on BHL at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/28198205#page/153/mode/1up

Brewster was very protective of the local muskrats, writing with obvious anger when their numbers dwindled due to hunting. Words like “murder” and “slaughter” were notably used to describe muskrat hunting starting in his 1890s journals. Around this time he seems to have developed a mindfulness of how damaging over-hunting could be for animal populations. He himself began to collect birds more sparingly and took up the challenge of wildlife photography.

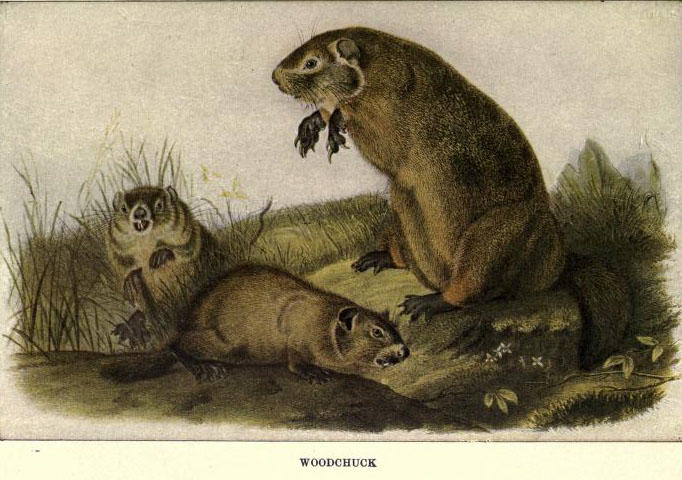

Some of that empathy comes across in an 1892 encounter with a woodchuck on the Concord River.

At about noon to-day as I was approaching the Ball's Hill landing a animal started out from the edge of the lily pads some distance in advance of me and headed directly across the river - here about 100 yds. wide.

At first I took it for a Muskrat but the head looked larger and was carried a little higher which as I approached nearer I could see a large dark eye showing conspicuously. The creature now perceived me for the first time and turned back although it had nearly reached the middle of the open water. I overhauled it quickly and found that it was a Woodchuck apparently of this season's birth but well grown.

When I came up with it it turned on me and floating quietly on the surface awaited what it must have thought to be certain death with the calm fortitude so characteristic of its race. The large, fine eyes met mine unflinchingly. Their expression was at once honest and fearless with nothing of the sullen desperation which gleams in the eye of the cornered Wolf or Fox nor of the piteous plea for mercy so unmistakable in the eye of the Deer or Rabbit when it is forced to face its pursuers.

Brave, self reliant creature! I had no trampled clover fields nor ravaged bean patches to avenge and I would not have harmed it for worlds. But I did tease it a little with my paddle chiefly to try if I could make it dive. It would not do this although once I pushed it quite under water. It met the paddle blade with open mouth showing its teeth threateningly and clashing them loudly but - to my surprise it did not once seize the wood or apparently try to do this.

When I drew off it slowly swam ashore and stood there dripping revealing more slender, graceful outlines than I had supposed any Woodchuck could possess. In fact with its fur thoroughly wet down it presented quite as symmetrical a form as that of a Gray Squirrel. After regarding me calmly for a few moments longer it plunged into the bushes and disappeared. (July 4, 1892. Concord, Mass.) [Edited with line breaks for readability.]

Illustration from ‘Squirrels and other fur-bearers’ by by John Burroughs. Boston; Houghton Mifflin company, 1909.

Viewable on BHL at: http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/57985#page/7/mode/1up

-Elizabeth Meyer